Level 17: Burj Dubai continues long climb into record books

Changing the skyline: The world’s tallest tower is expected to top the 800 m mark, dwarfing the skyscapers that currently dominate Sheikh Zayed Road.

CW explores how the challenges of construction are being met as the world’s tallest tower takes shape in dubai

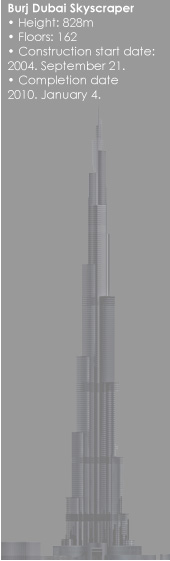

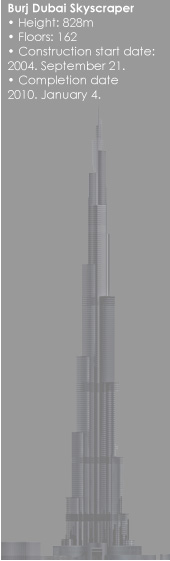

Currently standing at floor number 17, the Burj Dubai is slowly creeping towards its final height of 160 floors.

Approximately 250 000 m3 of concrete, 35 000 tonnes of steel and 40 000 trucks to deliver the concrete and steel to site are being used on the project.

To meet this logistical challenge, several new technologies are being employed in the design and construction of this US $3.2 billion leviathan.

The cranes and hoists; the concrete for the vertical elements; the speed of the lifts; and the formwork, all feature technology and methodologies which are pushing the construction boundaries.

The height of the Burj was originally penned at 723 m, but this has since been extended. Emaar is still keeping the final figure under wraps, but it is expected to top 800 m.

The additional height will be gained by extending the steel pinnacle that sits above the 575 m-tall reinforced concrete shaft core.

According to construction manager Saad Al-Joudi, design

restrictions mean the final height of the concrete section (154 floors) cannot be extended any more — wind tunnel tests have shown that people standing on the top floor of the Burj will be treated to a 1.6 m sway.

One factor limiting the height of the building is the capacity of the cranes — and the massive weight of the cables themselves.

Each of the three tower cranes on the Burj has a maximum lifting capacity of 25 tonnes, and each has a cable in the drum approximately 900 m long.

“The cable already weighs eight tonnes; if we extend the cable length, the weight of it will become unfeasible, so we do have a height limit which we cannot exceed,” says Al-Joudi.

Dismantling the three tower cranes will require a complex process. The first crane will be dismantled using the other two cranes; the third crane will dismantle the second crane; then jump form technology will be used to dismantle the final crane — which could take up to one month.

The design lifetime of the Burj is another achievement. While new regulations stipulate that a design lifetime should be 35 years or 40 years, the design lifetime of the Burj is 100 years.

All of the concrete used on the project is triple or four blends.

“The concrete quality used on the slabs is grade 35, and for the vertical slabs we’re using grade 80,” explains Al-Joudi.

The aggregates for the concrete come from the mountains of Ras Al Khaimah and Fujairah.

How to transport hundreds of people within the building is a crucial element in the tower’s design, with Otis winning the contract to supply around 60 lifts of different specifications in the Burj tower and ancillary buildings.

Triple-decker lifts — which would have been a world first — were at one time under consideration but this was later modified to double-decker lifts, and this will be the first time

that such lifts are installed in the Middle East.

The Burj will also feature some of the fastest lifts in the world: Two lifts will carry visitors from the ground floor up to the 120th floor in one minute (travelling at 10 metres per second).

While Austrian firm Doka is supplying the self-climbing

formwork for the Burj, Germany’s Hünnebeck is providing the plan and materials for the wall, soffit and joist formwork for the five to nine-storey podium area — in addition to the soffit and joist formwork for the first 10 storeys of the tower itself.

For the soffit areas in the podium and tower alone, Hünnebeck is supplying 9500 m2 of Variomax wooden beam formwork; almost 5000m2 of table forms; 900 ID 15 frame supports; and around 12 000 tubular steel props to the site.

All of this will be joined for the walls and columns by approximately 1000 m2 of Manto giant frame formwork, 14 Manto column sets and almost 700 m2 of Ronda circular formwork.

According to Frank Odzewalski, CEO of Hünnebeck Middle East, the main advantage of using the Manto giant steel-frame formwork on the walls is its aligning clamp, which connects the Manto panels flush with tension- and vibration-resistant joints in a single action.

“The easier the handling of the formwork equipment employed, the smoother the operations on site,” he says.

The aligning clamp permits the multi-panel erection, lining and moving of up to 40 m2 of Manto elements with a single crane lift, without having to fit extra stiffeners.

Another benefit of Manto is its frame thickness of 14 cm.

This and the interior stiffening ribs make the panels extra rugged and permit full-speed concrete pouring up to a height of 3.3 m.

Hünnebeck’s formwork is being used to produce the spindle-

like entrances and exits of the multi-storey car park — a task that calls for some sophisticated formwork engineering. The wall surfaces are being poured with Ronda circular formwork, which enables the creation of circular radii from 2.75 m upwards with millimetre precision.

In the areas where relatively large slab surfaces have to be shuttered (eg on the parking decks), Hünnebeck’s project planners recommended using soffit table forms. For the other slab areas in the podium — and particularly the first 10 slabs in the tower where small and confined areas need to be shuttered — Variomax wooden beam formwork is being used.

The Variomax system’s adaptability and versatility is particularly useful for the tower, which calls for the shuttering of joists of varying dimensions. Variomax is suitable for room widths of less than 2.65 m, slab thicknesses of over 30 cm and room heights of over 4.5 m.

On the project, the wooden beam formwork is being supported not only by tubular steel props, but also by ID 15 towers. In the multi-storey car park they are supporting the inclined ramps of the entrances and exits — with a footprint of just 1 m by 1 m. The load supports have an articulated bearing plate on the head and base jacks, which can cope with adaptation to pitches of up to 6%.

According to Odzewalski, the frame support is simple to handle: “Because none of the small number of parts weighs more than 19 kg, they are particularly easy to erect and dismantle. An ID 15 tower can be assembled to the desired height on its side on the ground, before being lifted upright and positioned by the crane.”

Odzewalski and his team were faced with a logistical challenge when delays caused the contracting JV to change the concreting cycle for the first 10 tower slabs.

Instead of pouring in succession (as originally planned), the second and fourth slabs were leapfrogged at short notice. This resulted in slab heights of almost 10 m, which demanded the rapid extension of the required number of ID15 supports.

As the Burj Dubai inches towards its accolade of being the world’s tallest building (as well as the world’s tallest man-made structure), the designers and construction teams are constantly finding new challenges to overcome.

“By the end of next year, we won’t be able to see the men working at the top of the structure from down here on the ground,” says Al-Joudi.

To counter this, the team is using satellite navigation systems from Leica to help ensure accurate levels of measurement and precise construction techniques.

“Seven control points have been planted within the steel piles on the site,” explains Al-Joudi. “These points are checked on site and counter-checked with another control system placed on top of a nearby building.”

The scale of the project means that logistics will play an increasingly important role as construction of the tower progresses and nears its scheduled completion date of December 2008.

“Currently there are 2300 construction workers on site; this figure will peak at around 8000 in August or September next year,” says Al-Joudi.

“The physical aspect of actually delivering the materials to site — not to mention raising them 800 m up — calls for some very close coordination,” adds Uwe Hinrichs, NSC/BWIC chief coordinator.

But since overcoming seemingly insurmountable obstacles

is a key element of this project, the task of coordinating materials for the half mile-high Burj will surely be par for the course.